-

29

May

We know that lots of parent-child book reading, pretend reading, and book browsing with traditional picture and storybooks promotes children’s development of literacy knowledge and skills in ways that support reading success (Mol & Bus, 2011). Reading storybooks exposes children to print and starts the process of learning how speech is written down. But can that very same process be nurtured when reading e-Books as children start to learn basic reading skills? Can parent-child sharing of e-Books help children gain an understanding of concepts such as, knowledge of letter names and how letters relate to sounds, identification of meaningful parts of words, awareness of book language as different from everyday language, and the insight that print has meaning? After all, at their core, e-Books are still books, right?

These very questions are some which I have been exploring with a small group of colleagues for the past 3 years. So, I was extremely excited to review the Cooney Center E-books QuickReport titled “Print Books vs. E-books.” The QuickReport explored parent-child interactions as they were reading print and/or digital books together. The Cooney researchers refer to this type of activity as “co-reading.” You can review the entire report on The Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop website. For those who are unfamiliar with the Cooney Center:

The Cooney Center is an independent research and innovation lab that catalyzes and supports research, development, and investment in digital media technologies to advance children’s learning. The focus of The Cooney Center is on literacy development for diverse learners. Programs address vital foundational capabilities, such as reading and writing, with a special emphasis on struggling readers who risk educational failure if they do not master basic competencies by grade 4. The Cooney Center is also focusing national attention on evolving “new literacies” that children need to compete and cooperate in the 21st century. Major initiatives focus on inter-cultural understanding, media literacy, and advancing Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) learning — all of which have become critical in an interconnected world.

The QuickStudy addressed these key questions.

- How do adults and children read e-books compared to print books?

- What might the nature of parent-child conversations differ across platforms?

- Which design features of e-books appear to support parent-child interaction?

- Do any features detract from these interactions?

Participants in the QuickStudy were parents and their children, age 3 to 6, who were assigned as sets to 1 of 2 groups. The first group co-read a print book and then co-read an “enhanced e-book.” The second group first co-read a “basic e-book” and then co-read a print book. The researchers define these different e-book types as follows:

…basic e-books, which are essentially print books put into a digital format with minimal features like highlighting text and audio narration, and enhanced e-books, which feature more interactive multimedia options like games, videos and interactive animations.

Findings from this QuickStudy:

- The enhanced e-book was less effective than the print and basic e-book in supporting the benefits of co-reading because it prompted more non-content related interactions.

- Features of the enhanced e-book may have affected children’s story recall because both parents and children focused their attention on non-content, more than story-related, issues.

- The print books were more advantageous for literacy building co-reading, whereas the e-books, particularly the enhanced e-book, were more advantageous for engaging children and prompting physical interaction.

I found this report to be extremely relevant and insightful. I really like the delineation between e-book types the Cooney Center researchers use. As Dr. Roskos, Sarah Widman and I reported in the Journal for Interactive Online Learning‘s “Investigating Analytic Tools for e-Book Design in Early Literacy Learning” back in 2009, eBooks for children come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Additionally, we concluded that not all eBooks are created equal. From that study:

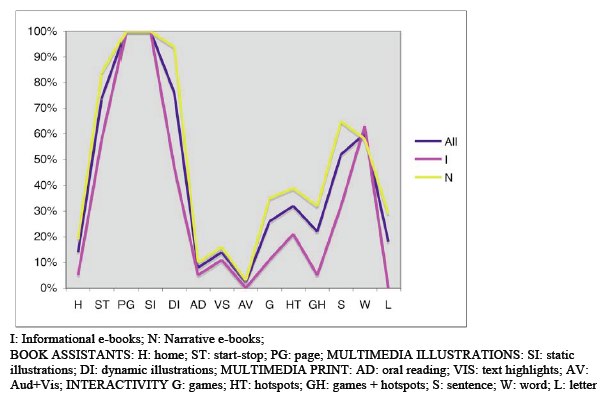

A survey of the analysis suggests a garden-variety design pattern that reflects the standard conventions of e-books for young children. Basics of book handling (Book Assists) are addressed across the sample in conventions of a home page (H), start-stop arrows (ST), and book-like pages (P). Although very few of the e-books in the sample included a distinct home page (12% All; 5% I; 19% N), most provided start-stop features at the screen page level (71% All; 58% I; 84% N). Navigation permits learner control primarily in page turning followed by starting and stopping the audio narration. Learner control is more prominent in narrative e-books as compared with informational e-books.

With respect to multimedia illustrations, nearly all illustrations in the narrative genre are animated in some way while this occurs in less than half of the informational books (100%; 47% respectively). Other than reading aloud, print is not supplemented by audio sounds and/or video very often in both genres (<20%). As a result, attention is directed to the gist of the written text, i.e., oral language comprehension, and not the print per se.

The emphasis on comprehension over print processing is also evident in the interactivity options. Nearly one-third of the narrative e-books include games/songs, hotspots or both to support comprehension (35%; 39%; 32%) although these devices are less prevalent in informational e-books (11%; 21%; 5%). Attention to print as an object of learning is primarily at the sentence level in narratives (65%) and the word level in informational texts (63%). Less than 30% of narratives moved to the letter level of print while informational texts in the sample did not reach this fine-grained of a level. All in all, the Tool I analysis reveals an e-book sample that reflects design features of traditional storybook reading implanted in the electronic environment.

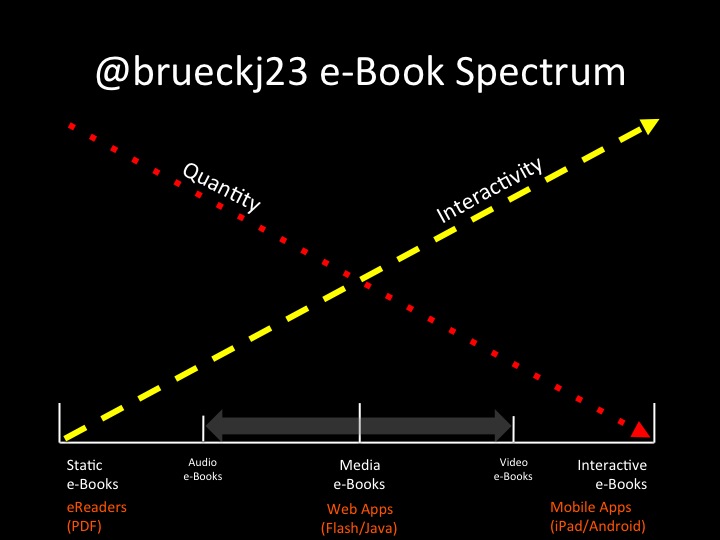

Because of this general garden variety finding, I normally tell parents and teachers that eBooks for early readers come in different types and stripes from plain and simple to bold and dynamic. In general, my research, which corresponds with the approach the Cooney Center has taken, suggests there are 3 main types of e-Books that vary depending on the kinds of digital interactive media they employee. I’ve created a 3 category spectrum of, static eBooks, media eBooks and interactive eBooks to illustrate. Let’s take a look.

Static eBooks: Often referred to as “eReaders.” Static e-Books are digital copies of traditional texts. Readers access the text using an eReader like the iPad, Nook or Kindle. eReader software sometimes provides enhancements like a search feature, highlighting & notes option.

Media eBooks: Encompassing a rather wide spectrum, Media e-Books can range from audio versions of a story to more of a movie-type presentation. Features may include narration, basic animations and print highlighting. These e-Books may be accessible through a web-browser or as a mobile app or file, and most often they are limited to “video player” functionality. [FWD/BACK, PLAY/PAUSE]

Interactive eBooks: As their name implies, these e-Books require varying levels of interaction between reader and book. Features range widely but can include: user-controlled animations, tap-to-hear word pronunciations, built-in dictionaries/definitions, games and puzzles

So, what does this all mean? I think it means that we have a long way to go before we can truly understand what the shift from print to digital means for our children. We need to better understand how eBooks impact the way we learn to read. Both the Cooney Center’s and our results point to a need for

tools that inform [eBook] design in ways that lead to more careful, more thoughtful, more functional e-books that support early literacy learning cognitively and affectively.

In conclusion, there is a lot more that we need to know designing high-quality eBooks for young children, but maybe more importantly, the most effective ways to use these eBooks to support the learning of our youngest readers.

REFERENCES

Mol, S. E., & Bus, A. G. (2011). To read or not to read: A meta-analysis of print exposure from infancy to early adulthood. Psychological Bulletin. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a00218

Roskos, K., Brueck, J., & Widman, S. (2009). Developing analytic tools for e-book design in early literacy learning. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8, 2009. Internet Available: http://www. ncolr.org/jiol.

- Published by brueckj23 in: Raised Digital University of Akron

- If you like this blog please take a second from your precious time and subscribe to my rss feed!

Leave a Reply